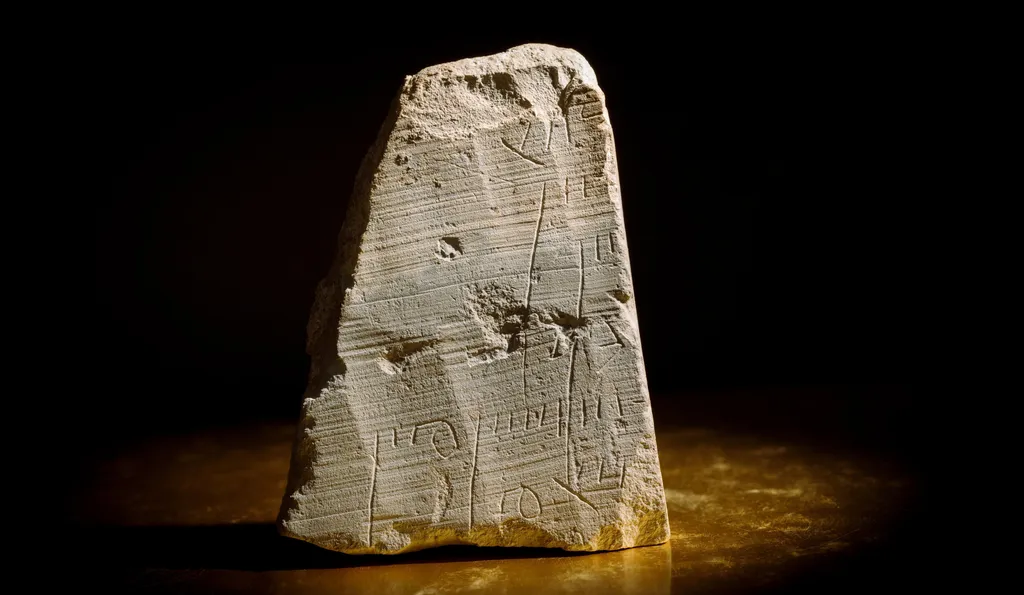

About 120 years ago, two British archaeologists doing excavations in ancient Jerusalem did not discover the inscription dating to the Early Roman period that the Israel Antiquities Authority unveiled on Wednesday. They left it undiscovered, but the late 19th-century trench where Israeli archaeologists working with the antiquities authority found it this year was dug by these two Brits – Frederick Jones Bliss and Archibald Campbell Dickie.

The inscription is on a broken fragment of limestone tablet. It consists of seven fragmented lines written in Hebrew, alongside numbers. This, the Israel Antiquities Authority suggests, is a financial record from about 2,000 years ago. It could be a receipt, in theory.

This isn’t the first financial record from antiquity to be found in Israel. Nahshon Szanton, the authority’s excavations director, and epigraphist Prof. Esther Eshel of Bar Ilan University, list four similar Hebrew inscriptions in an article in the archaeological journal ‘Atiqot. All were found in the vicinity of Jerusalem and the nearby city of Beit Shemesh, and all contain names and numbers, written on stone tablets and dating to the early Roman period.

But this is the first to have been found in the core of ancient Jerusalem itself, the authority says – and on the city’s main drag, the Roman-era Stepped Street leading to the Temple Mount, no less. In a trench left by Bliss and Dickie 120 years ago.

The Stepped Street pilgrimage route is thought to have been built by Pontius Pilate and is believed to have only been in use for a few decades before being covered in debris from the Roman destruction of Jerusalem.

Enter Shimon

Eshel’s interpretation of the writing suggests that one line contains the end of the name “’Shimon,” followed by the Hebrew letter mem.

What can actually be seen are the letters ayin, waw and nun sofit. Asked why they think the name is Shimon and no other, Szanton says they can’t be sure, of course. But Shimon was one of the most common names in the early Roman period in the area, perhaps the most common. “It’s a probability that we suggest,” he clarifies.

Other lines contain symbols representing numbers, some preceded by letters that the archaeologists believe define monetary values: the letter mem as abbreviation of ma’ot and resh as an abbreviation of reva’im. “It’s like denominations of shekel and agora [or dollars and cents],” Szanton says. Both signify amounts, but different amounts.

How is it that Bliss and Dickie left this precious financial record from yore in their trench, or failed to notice it? Probably because of their antiquated methodology. Nineteenth-century archaeology involved digging trenches, roughly shoulder wide and a few feet deep, and throwing the dirt from a new trench into an old one, Szanton explains.

“So they left a lot of material behind,” he says. “They basically left behind everything other than intact, remarkable pieces, some of which they took and some of which they published.”

Actually, the modern archaeologists wouldn’t have realized it was an inscription, rather than just a piece of broken stone slab, because – like all things buried for centuries and millennia – it was filthy. They would have had no understanding of its actual value. The Israeli archaeologists only saw the writing after the fragment had been cleaned, Szanton says.

So why did they clean it if they didn’t see anything on it? It’s because they clean all items they find in the excavation, he explains.

The broken sarcophagus

The context of the discovery supports the interpretation of this piece as a financial record – it was found in the lower square of the ancient city of Jerusalem, along the Stepped Street, which was a key artery in ancient Jerusalem, the antiquities authority says. Ruins of shops and homes along it attest to that area’s commercial nature.

It is true that having been found in previous archaeologists’ trenches, the fragment was not in situ, not in its original place. But it could still be dated to the early Roman period by the type of script, the type of stone slab, and its similarity to other inscriptions of the time.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect is the possible provenance of the stone. Szanton speculates that it may have originally been (part of) the lid of an ossuary, meaning, a stone chest that would have served as the final resting place for a person’s bones.

The fragment is part of a bigger piece, which had been flat and thin, Szanton says.

He isn’t suggesting that the lid was improperly acquired, but rather that it broke and this piece was repurposed. It would have been a readily accessible material in that time and place. The stepped pilgrimage road could have had stores selling that very thing – burial boxes. And the soft stone is perfect for a quick scribble.

Note that financial records from the Roman era aren’t even close to being the earliest. That honor goes to finds in Mesopotamia aged around 4,000 years that lists receipts, disbursements, contracts, pledges and whatnot. That’s also where archaeologists found a letter with an early customer complaint, from a person named Nanni grousing to a merchant named Ea-nasir in the city of Ur 3,750 years ago about his lousy copper ingots, and discourtesy to his envoy to boot.

Some things never change. But even though a mere list of names and numbers sounds comparatively dull, it actually sheds rare light on everyday life in ancient Jerusalem 2,000 years ago. Maybe it was a receipt, just like we get at stores today, when the merchant isn’t avoiding taxes.

Original Article – Israeli Archaeologists Find 2,000-year-old Financial Record in Jerusalem – Archaeology – Haaretz.com